Derek Fung

BYD Atto 3: Much more powerful rear- and all-wheel drive models approved for sale

2 Hours Ago

Contributor

In the 1980s, buying a luxury car generally meant purchasing something European. Apart from the usual Mercedes Benz S-Class and BMW 7 Series, the Jaguar XJ, and perhaps various Bentley and Rolls-Royce options, there wasn’t much else.

Models from Lincoln and Cadillac were restricted to the American market, and couldn’t hold a candle to their European competition with regard to quality.

Japanese exports during this time were generally cheap, reliable, and effective transport, but not necessarily the last word in luxury. Often, a customer would graduate into something European when they wanted more than just basic transport.

Toyota aimed to change the rules with the Lexus LS. Taking more than five years to develop, with over 450 prototypes built that were cumulatively tested over more than 3.5 million kilometres, Toyota spent more than US$1 billion making the original LS.

The result was nothing short of stunning, with the LS pioneering numerous innovations to challenge and beat the Europeans at their own game.

Sometimes derided as an acronym for ‘Luxury Exports to the US’, Toyota proved with the Lexus LS it had the engineering chops to take on the world’s best.

Core to any luxury car are minimal levels of noise, vibration and harshness (commonly referred to as NVH). In an automotive context, these three characteristics are the definition of smoothness.

Good NVH equates to a quiet, comfortable car that is easy to drive in a relaxed and refined manner.

The Lexus LS made use of numerous drivetrain and suspension technologies that may not have been world firsts in their own right, but were combined successfully into a cohesive whole that surpassed its competitors.

One of the most important innovations was the use of separate ECUs for the transmission and the engine. Most cars feature at least one ECU (electronic control unit) to control the ignition behaviour of the engine.

Having separate ECUs for the transmission and engine enabled both to be networked, such that when a gear change was about to occur the engine would momentarily delay combustion, reducing torque output and facilitating smoother changes.

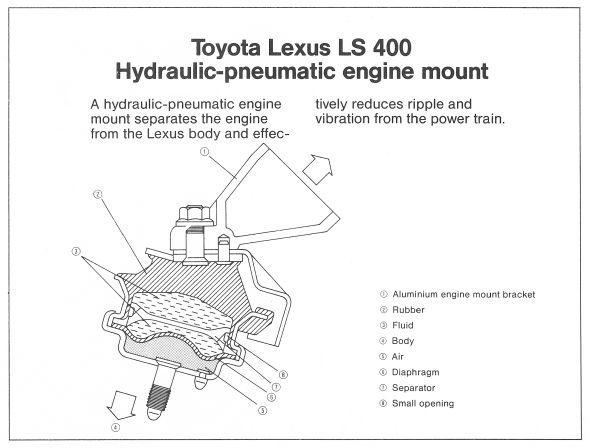

Vibrations from the engine were further minimised by isolating it from the rest of the car. This was done by placing the engine on its own hydraulic mounts.

Similar in principle to the hydropneumatic suspension systems used on the Mini and Citroën DS, these mounts effectively served as a miniature suspension just for the engine, in order to dampen and prevent vibrations from flowing to the rest of the car.

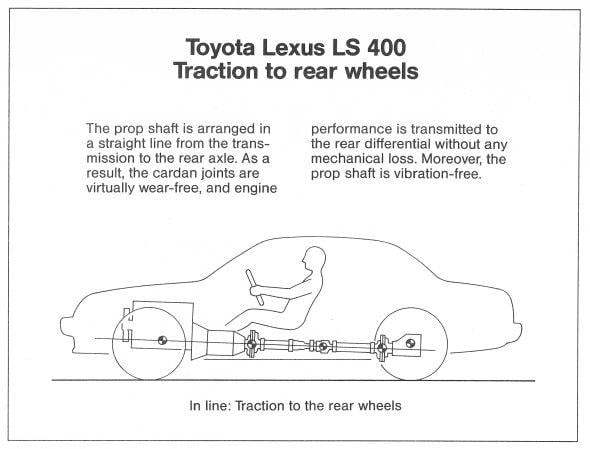

Overall NVH was additionally improved by tilting the engine back within the engine bay. This geometry provided space for the driveshaft to be aligned with the transmission to not only mitigate any mechanical power losses, but also reduce vibration further.

Air suspension systems and power steering had featured in vehicles before, but the LS was among the first to link both to parameters such as vehicle speed. The self-levelling, computer-controlled air suspension would automatically change its ride height to optimise aerodynamic efficiency at higher speeds, and the level of power assistance for the steering would change to make the car easier to manoeuvre at lower speeds while retaining a natural feel when driving more quickly.

A stiff, rigid body with minimal panel gaps pays dividends for dynamics and handling, and can also facilitate a reduction in vehicle weight by requiring less sound-deadening to achieve an equivalent level of NVH.

The LS was a pioneer in this regard. Key was its innovation of laser welding. Rather than traditional, heat-based welding guns, LS production made use of high-energy lasers to bond various strength steels together.

With welds 1.5x stronger than conventional techniques, this facilitated the production of a stiffer body. As a side benefit, the use of laser welding meant Toyota was able to get rid of the visible weld lines typically found within the door enclosures on other cars, lifting visual perceptions of quality.

The production process itself was outstanding in its attention to detail. The LS was one of the first models where each example had computer-controlled panel gaps to ensure consistency, with gaps between panels in some areas being deliberately tapered for a more pleasing appearance.

During assembly, line workers were trained to listen for a specific clicking sound when installing various parts such as the door frames. Vehicle production could move onto the next step only if this sound was heard, regardless of how well the part looked attached.

Marques such as GM, Mercedes-Benz, and Porsche had all introduced airbags in certain models in the late 1970s and ’80s, but Lexus was the first to include a driver’s airbag within a reach- and rake-adjustable steering wheel. For ease of entry, the wheel itself could move out of the way after the car had been turned off.

More on the cool side of things but officially claimed to reduce eye strain and improve legibility, the LS introduced Lexus’ trademark ‘Optitron’ gauges.

Using the same principles as an older cathode ray tube (CRT) TV, these gauges featured glowing cathode tubes rather than traditionally backlit needles, creating a glowing effect that made it easier for the driver to read the speed at night.

Go deeper on the cars in our Showroom, compare your options, or see what a great deal looks like with help from our New Car Specialists.

Derek Fung

2 Hours Ago

Ben Zachariah

9 Hours Ago

Ben Zachariah

9 Hours Ago

William Stopford

14 Hours Ago

William Stopford

16 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

18 Hours Ago

Add CarExpert as a Preferred Source on Google so your search results prioritise writing by actual experts, not AI.