Damion Smy

Toyota says it has "no update" as it works to combat HiLux, LandCruiser thefts

13 Hours Ago

By using connected vehicle data points around braking, accelerating and swerving, you can proactively find black spots or hazards.

Senior Contributor

Senior Contributor

We hear a lot about ‘connected cars’ and the growing importance of vehicles with clever sensors and access to the cloud, but sometimes the topic gets hobbled by buzzwords.

Connected cars are connected to the internet, meaning they access over-the-air updates and downloadable apps among other things. Bi-directional transmission means cars can also send their data to a cloud and central management system.

This gives people a way to keep their cars up-to-date or create a revenue stream for car brands. But its potential goes beyond this: it can also make roads safer and less congested.

Australian road intelligence company Compass IoT (Internet of Things), co-founded by Emily Bobis and Angus McDonald, last year picked up gongs from Google Cloud and the Australian Small Business Champion Awards.

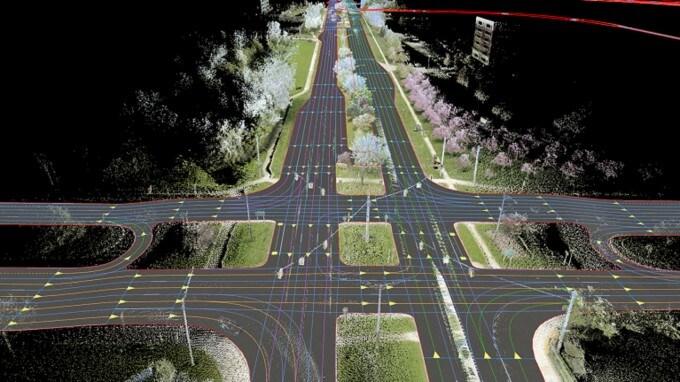

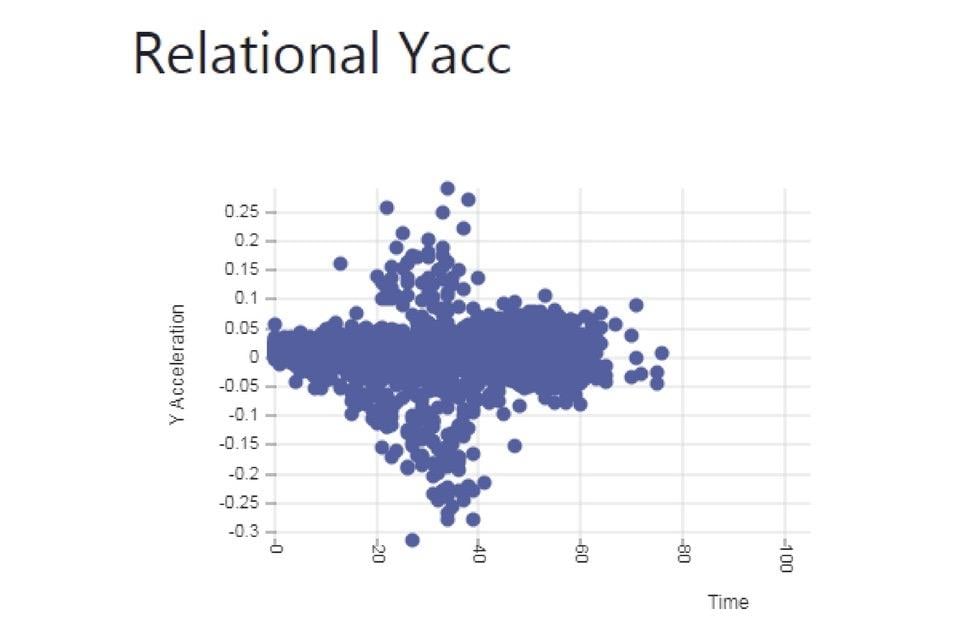

Compass aggregates anonymised vehicle performance data from 64 car brands – so, most of them – which come from embedded sensors via onboard SIMs, or via retro-fitted telematics on older vehicles. From there machine learning spots resultant trends and patterns in traffic flow.

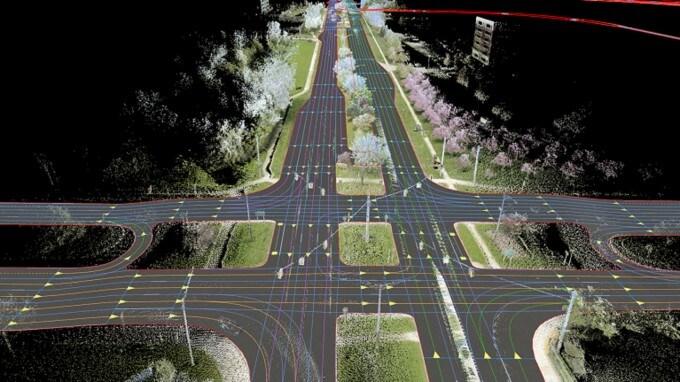

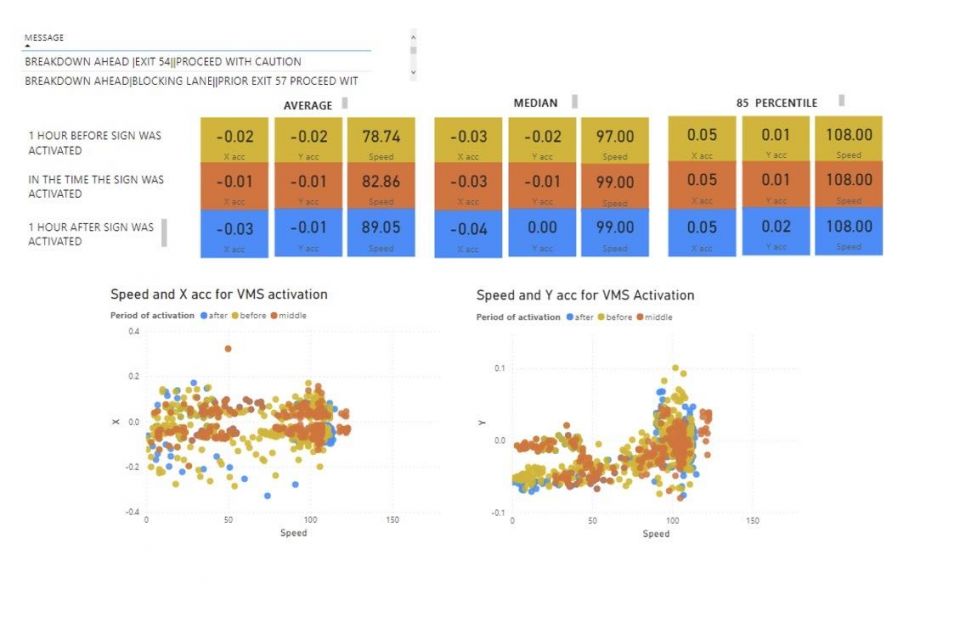

That means recording and sharing things like braking, swerving, pitch, roll and yaw at scale, allowing the right sets of eyes to identify transport pinch points or potential blackspots – before they become blackspots.

The company says its data set has doubled every year for the last four, and now maps 2.2 million trips per day totalling about a billion data points. These are mapped out as dots on graphs and maps, from which trained eyes can infer all sorts of situations from car behaviours.

This is billed as a more proactive and accessible approach than traffic surveys using tube counts, cameras, or requiring manual volume counts. It has therefore grabbed the attention of local councils, road operators, state governments, researchers and insurance companies.

“There wasn’t enough data about how people actually moved around cities that was reliable and scalable. So, in September 2018, we launched Compass IoT and worked on it between casual jobs and uni classes,” said the company’s founders.

We spoke with co-founder Emily Bobis, who said older forms of road intelligence gathering required higher overheads and couldn’t go as granular as Compass IoT’s dashboard.

“A near miss is a harsh braking or swerving event measured at a high G force, which lets you proactively identify areas that are at high risk of a crash. A cluster of near misses [is suggestive],” Ms Bobis told us when asked to provide an example of how to best use the data.

A few case studies using Compass IoT include:

Of course, there are questions. For instance, what about data privacy?

“There’s always questions about Big Brother,” Ms Bobis acknowledged. “We aren’t tracking people, [but rather] car movements on aggregate,” she added.

There are privacy constraints applied to the data, including clipping the origin and final destination of a vehicle. VIN data is never collected, stored, or used without explicit unambiguous consent from vehicle owners, the company adds.

In terms of frequency, it claims data pipelines of latencies under 100 milliseconds, so customers using the real-time API can receive data every five seconds or so. Compass says it now has connected vehicle data across virtually every road in Australia.

What comes next? One key potential application of connected car data includes tracking EV use, which public-charge providers can use to work out the best places to place stations and get a quick return-on-investment, Ms Bobis claims.

Of course, it’s not just companies like Compass exploring the potential safety benefits of connected cars.

For instance the Mercedes-Benz E- and S-Class use car-to-car communication to warn the following vehicles of unexpected risks such as imminent black ice or an accident.

Audi’s vehicle-to-infrastructure system meanwhile works by letting drivers know their ideal speed to catch the green light and also the time until the next green light. If stopping at a red light is unavoidable, a countdown displays the seconds remaining until the next green phase.

Skoda is also working on a robotic ‘lollipop lady’ called IPA2X designed to communicate with vehicles via an animation on the infotainment system.

It will display a message when pedestrians are approaching a crossing or are already on it.

Damion Smy

13 Hours Ago

CarExpert

13 Hours Ago

Alborz Fallah

14 Hours Ago

Derek Fung

16 Hours Ago

Max Davies

22 Hours Ago

James Wong

1 Day Ago

Add CarExpert as a Preferred Source on Google so your search results prioritise writing by actual experts, not AI.