Damion Smy

2026 Volkswagen ID. Polo EV spied along with ID. Polo GTI electric hot hatch

6 Hours Ago

Over the air updates have the potential to significantly improve your car. But how do they work and what can they change?

Contributor

Contributor

Cars have primarily been ‘hardware’ products. The car-maker builds the vehicle in a factory, and the buyer purchases it from a dealer.

If they would like to make any further changes or improvements, the owner would usually have to take it to a mechanic or then aftermarket, or buy the requisite parts and tools to do it themselves.

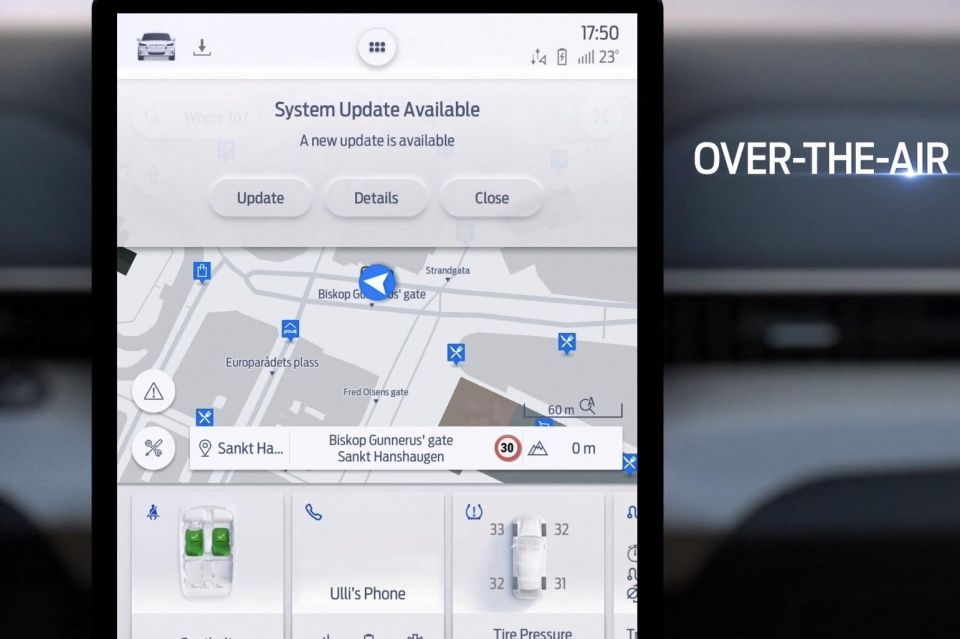

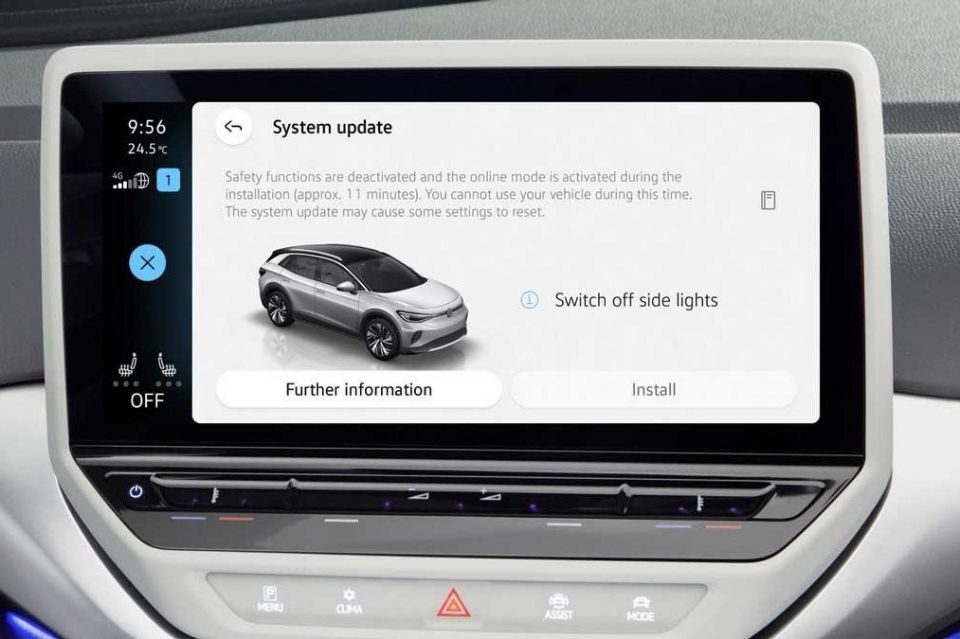

By contrast today’s vehicles are becoming increasingly computerised and run sophisticated software that can connect to the Internet, via an inbuilt modem or through Wi-Fi. This allows changes to be made much more easily through ‘over-the-air’ (OTA) updates, much like updating apps on a smartphone or the software on a laptop.

Whilst the basic principles of over-the-air updates are shared between cars and other computing devices, what can actually be updated still varies widely between models. This includes anything from a simple map update for the car’s in-built sat-nav system, to the car’s driving performance changing, to the addition of entirely new features.

Much like the actual scope of what can be updated, the process of updating your car, and the frequency with which updates are released, varies widely depending on the car maker.

At a fundamental level, the carmaker will upload software updates to a central server, that the car’s onboard computers can access via an in-built 4G/5G modem, or when connected to the Internet via Wi-Fi.

If a car detects that an update is available, the driver will be given an option to download it. Depending on various factors such as how the car is connected to the Internet (as aforementioned) and the type of software that the car runs, it may be able to download an update in the background whilst driving, or the car may be required to be at a standstill.

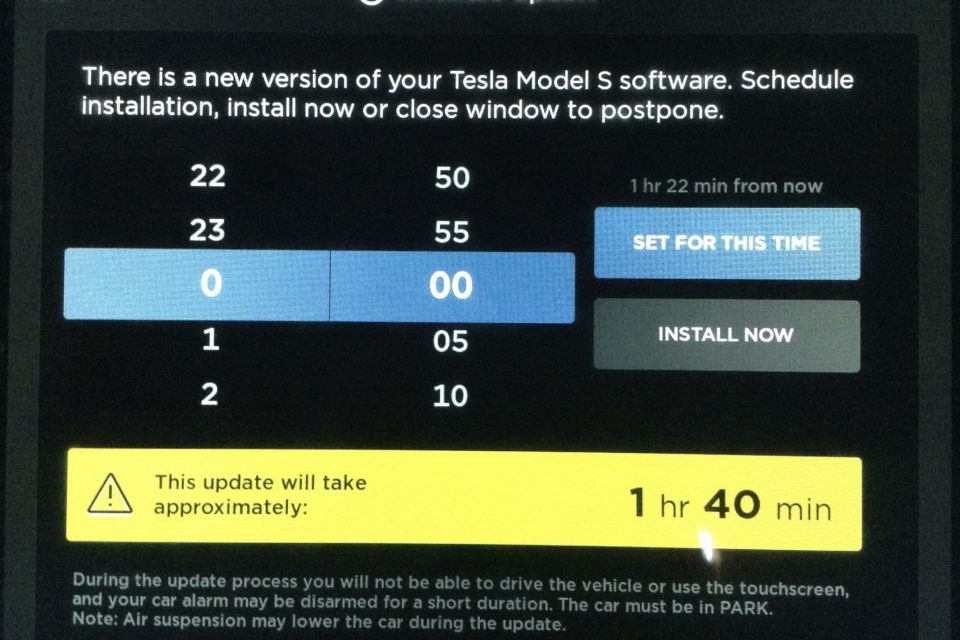

In many cases, such as with various Tesla vehicles and BMW models running newer Operating System 7.0 and 8.0 software versions, the car cannot be used at all whilst an update is being installed.

To compensate for this, most car makers allow the driver to schedule when they would like the update to be installed. For example, the car could download an update in the background (and be used normally), but then the driver can schedule the installation to occur overnight when they know the vehicle will be parked and not in use.

The frequency of updates also varies widely across models. For many entry-level vehicles, the only part of the car that can be updated OTA are the maps for the in-built sat-nav system. These updates may be released on an annual or biannual basis. Other manufacturers may release updates more frequently. Tesla for example, rolls out updates on an almost monthly basis.

In today’s vehicles, many parts of a car, including everything from the engine (or motors in an EV), battery cooling systems, brakes, infotainment system and other aspects are controlled by computers or associated electronic modules. The scope of what an OTA update can do depends on whether these modules have been engineered to be updatable via the Internet.

As mentioned previously, for some cars, the only aspect that can be updated are the maps for the in-built sat-nav system. For other cars, a wide variety of subsystems can be updated.

Polestar (associated with Volvo) for example has recently released updates for its Polestar 2 sedan that have improved the car’s range, and for Long Range versions, its performance as well. Tesla has gone as far as updating the ABS (anti-lock-brakes) system in its Model 3 sedan and improving stopping performance from 60mph (97 km/h) by approximately 5.7 metres, after US publication Consumer Reportscriticised the car’s braking performance in 2018.

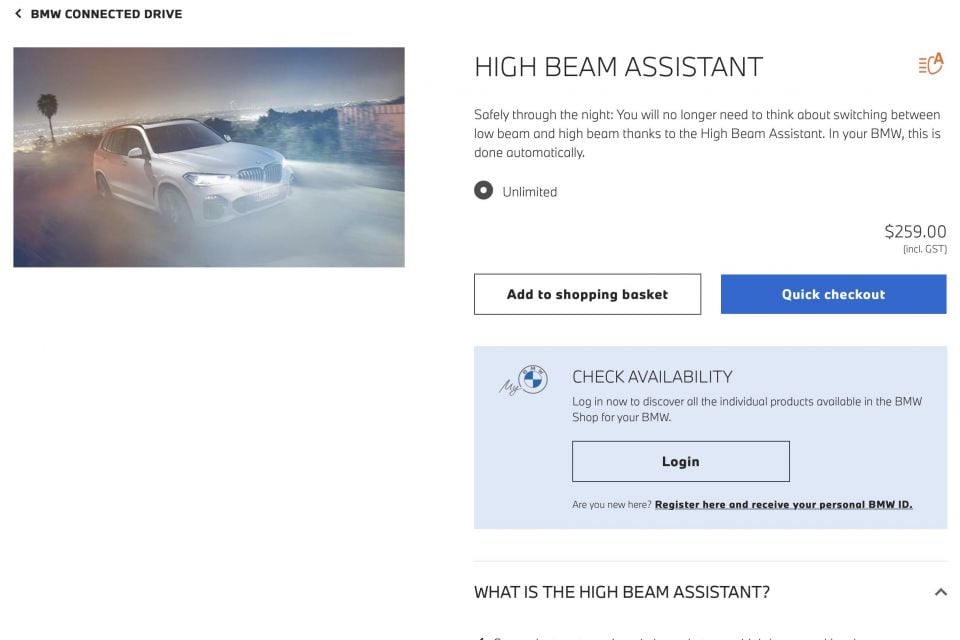

Widening the scope of what electronic modules can be updated via the Internet also gives the potential for drivers to unlock or add features over-the-air. BMW, for example has a ‘ConnectedDrive App Store’ through which drivers can download software OTA to enable features such as the High-Beam Assistant or the BMW Drive Recorder dash-cam feature.

Apart from certain models from Polestar, Volvo (such as the XC40 Recharge EV), BMW and Tesla, other carmakers that have introduced models which have a wide variety of systems that can be updated OTA include MBUX equipped vehicles from Mercedes-Benz (such as the new EQS), and Ford vehicles equipped with the Sync 4 infotainment system. VW’s latest ID. 3 and ID. 4 models (not currently sold in Australia) also feature OTA software updates.

The upcoming Ford Ranger features a new infotainment system, and Ford claims that the car overall includes more than 50 electronic modules that can be updated OTA.

This could mean that Ford could release various OTA updates over the model’s lifecycle that enable prospective owners to download new features, or make improvements to everything from the infotainment system to the car’s on and off-road driving ability.

Given the Ranger is one of the two biggest-selling vehicles in Australia, any OTA capability will help introduce the technology to a lot more people.

As implied previously, the greatest advantage of OTA updates is the ability to future-proof the car by improving it after it has been built. OTA updates now give manufacturers the potential to improve the car’s safety, usability, functionality and performance over time.

All of this can help ensure that a car remains up to date with current technologies despite an older build date, and in turn, this could have a positive contribution to the car’s resale value as well.

On the flip side, armed with the knowledge that things can be improved later on, car manufacturers may be incentivised to sell what is a minimum viable product with the promise of subsequent improvements or addition of full functionality.

Perhaps the best illustration of this is to reiterate the Tesla Model 3 braking example. It is applaudable that Tesla was able to improve braking performance (and thereby safety) easily and after cars had been built, and customers were not inconvenienced by having to take their vehicles to a service centre or go through a recall process.

However, if Tesla did not have the capability to perform OTA updates, it would arguably have been forced to optimise and test braking performance from the get-go, rather than deferring it to something that could be improved later.

A similar situation has applied to VW’s ID.3 electric vehicle. Early batches of these cars suffered from a rushed development process and numerous software issues, which the German manufacturer promised to resolve via OTA updates.

MORE: We have pages of these technical explainer articles, all located here

Damion Smy

6 Hours Ago

William Stopford

7 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

9 Hours Ago

Ben Zachariah

10 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

11 Hours Ago

William Stopford

11 Hours Ago

Add CarExpert as a Preferred Source on Google so your search results prioritise writing by actual experts, not AI.