Damion Smy

Ford posts its biggest loss since the Global Financial Crisis

3 Hours Ago

Contributor

The Fiat 500 launched in 1957 as the ‘Nuova’ (new) 500, a successor to the pre-WWII model that despite also bearing the 500 name, was almost always known popularly as the Topolino.

It’s important to remember Italy in the 1950s was in a reconstruction phase. The economy, and the country as a whole, had been devastated by the horrors of WWII, with incomes low and basic resources and materials in short supply.

The new 500 then wasn’t conceived as a competitor to other vehicles, or designed to bring people from larger, less fuel-efficient cars into a smaller alternative.

Instead, perhaps its main competitors at the time were Vespa scooters and motorcycles that had been used as family transport. The purpose of the 500 was to get Italians into the relative safety and practicality of a four-wheeled vehicle as cheaply as possible.

Much of the technical innovation and utilitarian design of the 500 was therefore driven by cost and material constraints.

That these constraints also resulted in an attractive, iconic silhouette distinctly recognisable the world over is testament to the ingenuity of Italian design and engineering.

It may seem odd to begin a discussion of a car first introduced in the 1950s with the topic of aerodynamics. However, even back then it was well established that cars with less drag moved through air more easily and offered better fuel economy which, in resource and cash-strapped Italy, would be a critical selling point.

Key to the aerodynamics of the 500 was its small size and rounded profile. At only 2.9m long and narrow enough to fit inside Italy’s tiny medieval city streets, the 500 had a drag coefficient (Cd) of 0.38.

Aerodynamics is just one factor of the efficiency equation, with weight also playing a key role. In post-war Italy, steel remained expensive and in short supply.

For this reason, all 500s initially came standard with a fabric roof, with a full-metal roof not available even as an option until later in the car’s life. Fabric is lighter than steel, and this meant less mass for the engine to push around and better fuel economy.

Of course, Fiat’s marketing department ignored any detriments the fabric roof had to body rigidity and sold the car as a convertible, with all the ‘fun’ benefits that go with it.

In such a small car the more useful advantage, however, was the improved practicality afforded by the opening roof. The 500 could transport tall items by simply sticking them out the top.

All of this enabled a fuel consumption of around 4.5L/100km which, while high on a power-to-economy basis by modern standards, was very low at the time for a car that could reach 85 km/h.

As a yardstick to show how far technology has advanced in 60 years, the new Toyota Yaris Cross hybrid offers a fuel economy of 3.8-4.0L/100km despite being substantially heavier and producing 85kW compared to the original 500’s 9.7kW!

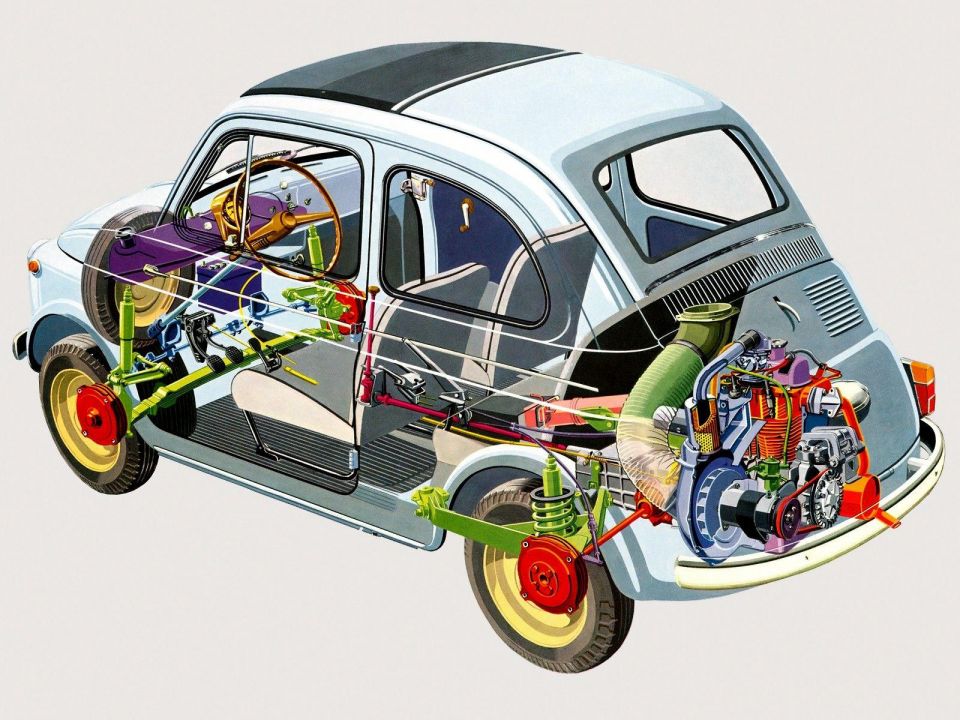

Simplicity and compactness were the overarching principles of the 500’s drivetrain design. While front-wheel drive (FWD) cars were increasingly becoming popular, rear-wheel drive remained an ideal option for the city.

FWD cars must accommodate hardware such as CV joints and other components to transfer power from the engine to the front wheels, which reduces the flexibility of the wheels to turn.

In a comparable RWD car the front wheels are not the drive wheels, leaving them un-compromised by the additional hardware for greater articulation and a smaller turning circle to easily navigate tight streets.

Having decided which wheels would drive the car, the next decision for the 500’s engineers was where to place the engine. A typical front engine, rear-wheel drive layout would require a driveshaft and transmission tunnel, creating a hump through the middle of the car and reducing interior space.

For this reason, the 500 found itself using the same fundamental drivetrain concept as the Porsche 911 – a rear engine, rear-wheel drive layout. This also served to improve traction on slippery surfaces, as the heavier engine pushed the driving wheels into the pavement.

The 500 used a simple, two-cylinder air-cooled engine (as opposed to contemporary vehicles that are water cooled with a fluid known as the coolant) with displacement of 479cc on early models. Whilst the engine itself wasn’t the last word in refinement or smoothness, it was mounted on its own coil spring to reduce the vibrations and harshness entering into the cabin.

The transmission, a 4-speed manual, remained a crude affair, lacking a synchromesh on all gears until late into the 500’s production run.

Unlike modern manual cars where the driver can change gears simply by depressing the clutch and selecting the next gear, 500 drivers had to use a more complex technique known as double de-clutching. This involved depressing the clutch first, and then moving the shifter into neutral before the next gear could be selected.

Go deeper on the cars in our Showroom, compare your options, or see what a great deal looks like with help from our New Car Specialists.

Damion Smy

3 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

3 Hours Ago

Ben Zachariah

5 Hours Ago

William Stopford

6 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

9 Hours Ago

William Stopford

9 Hours Ago

Add CarExpert as a Preferred Source on Google so your search results prioritise writing by actual experts, not AI.